This hurricane season has been a stark contrast to the last one to say the least. It has been a slow start as well; so far, it’s been the slowest peak season since 1939. The main contrast from last year is the lack of strength in storms. At the time this article was written, only six storms have formed this season. So far, Erin as a Cat 5 and the rest of the storms being weak and barely organized tropical storms either in the middle of the Atlantic or by the U.S or Mexican coast forming off cold fronts. Chantal and Barry have been the only landfalling storms of the season as weak tropical storms. It begs the following question: What has made this season so quiet, and will it stay this way?

This season was expected to be active, especially in September. This year, a global climate pattern, La Nina, occurred. This is when the waters near the equator in the Pacific experience cooler temperatures. This causes drier conditions for the Pacific coast, the southeast U.S, and more wind shear for the gulf. In layman’s terms, it is essentially stronger winds in the upper atmosphere which tear apart the clouds in a storm. It makes the Atlantic and Caribbean favorable for hurricanes because of the lack of shear in those areas, which explains why the NHC and NOAA speculated this to be an above average season, especially due to a warmer climate.

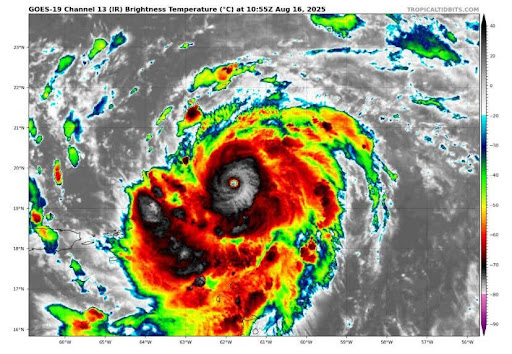

However, if this season had a strong setup for storms, then what is stopping them? La Nina is not particularly strong, but storms have been demonstrating what would typically be unfavorable regarding conditions in other years. It seems to be the main culprit that has been limiting development in the Atlantic. That’s been the main talk this season. This summer in particular, the Saharan dust mass has been far more prevalent and widespread. What this dust does is cut off fuel for the storms, as it is very dry air that prevents the moist ocean air from maintaining or even forming the storms that later come together into hurricanes. It has choked almost most of the tropical waves that have come off Africa, and in the earlier parts of the summer even in the Gulf. Hurricane Erin almost didn’t happen because of the dust as it fell apart after leaving Africa before finding a gap in the dust which allowed for its explosive intensification. Essentially for the Atlantic basin the unusual prevalence of dust has simply prevented systems from surviving the long trip across the tropical Atlantic.

The gulf and the western Caribbean this season are what has had the spotlight because of Helene, Milton, and Rafeal all forming and exploding there last year. The odd thing is, it’s been the quietest region. This is due to La Nina since it quells activity in the gulf from the wind shear that would otherwise be in the Atlantic and Caribbean. This essentially has made any storms unable to organize. There have been storms trying to organize off cold fronts but because of the shear they cannot form the proper circulation and structure as it keeps the clouds more spread out. Despite the steaming ocean temperatures, nothing organized has popped up.

What does the rest of the season hold? Currently not much. The cold fronts that have brought noticeably less miserable conditions to St Pete and are essentially keeping any storms that form in the Atlantic and stay north of the Caribbean away for the time being, and the dust keeping them from forming in the first place. NOAA is currently predicting less tropical waves forming and moving far west until early October because of a global monsoon pattern which also keeps anything from making its way to the Caribbean and forming there as it is the main area of concern since almost every storm that has threatened Tampa Bay has come from there. However, last year was slow too this time of year and then October came along. Never say never is a widely used phrase in hurricane forecasting, but for now it can be said that a strong storm with the likes of Helene, Milton, Ian, or even Irma that threatens the bay is currently not likely for this year if this pattern continues.